Before coming to study in the Netherlands, we thought that the education was very similar to what we were used to in Spain, but we were surprised to realize that there are many more differences than we expected.

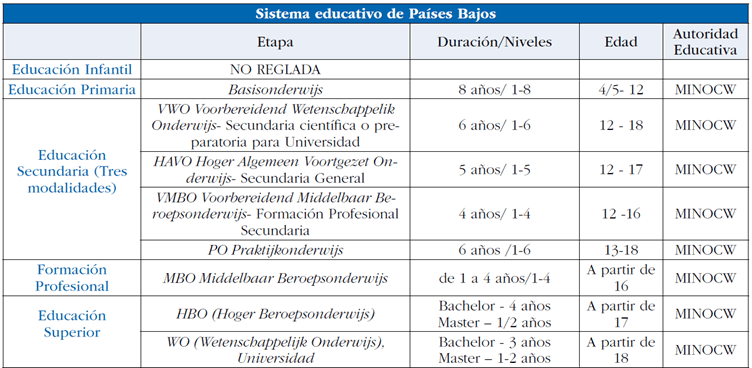

First of all, already in Secondary Education the students are divided much earlier than in Spain. They are not only divided into “sciences” or “letters”, but already at the age of 12 (corresponding to the first year of ESO in Spain), the Dutch have to choose whether they want to go to university or follow a more practical education. Specifically, there are three types of secondary education: university (VWO), general (HAVO) and vocational secondary education (VMBO) (ref 1). In addition, the type of secondary education to be pursued is established according to the results of the final primary school exam, at age 11-12. Thus, the result of a single exam taken at such a young age will decide whether the student will go to university or not. Of course there are ways to switch between types of education based on the grades you get, but this is not always easy. This situation is very different from ESO in Spain, where everyone has to take the same type of education until they are 15-16 years old, and then they decide between the bachillerato, oriented towards university education, or the grado medio, oriented towards vocational training.

There are also differences in the Dutch university system. There are universities as we know them in Spain, oriented to theoretical and research training, but there are also the so-called “colleges of higher education” or Hogescholen, which could be compared to higher degrees, but also include degrees that in Spain are university degrees, such as engineering and other technical sciences. In addition, while in Spain most degrees are 4 years (240 credits), in the Netherlands they are usually 3 years (180 credits). However, in the Netherlands the bachelor’s degree is usually accompanied by a 2-year master’s degree, while in Spain the master’s degree is usually one year. Therefore, in total, bachelor’s and master’s degrees in both countries add up to a total of 5 years. This is something to consider if you decide to come to the Netherlands to study a bachelor’s or a master’s degree, because in the end you may end up studying 6 years, which is what happened to us.Also curious is that university courses are not organized in semesters or quarters as in Spain (from September to December/January, and from January/February to May/June), with several subjects per semester. On the contrary, the Dutch courses are organized in so called periods of 2 months duration, with 2 subjects each period, and exams at the end of those 2 months. This from our point of view has some disadvantages, such as less time in general to dedicate to the subjects (as there are more weeks of exams and therefore less weeks of class), and less time to consolidate the contents. On the other hand, you can focus more deeply on the subjects during this period. Another great advantage, which is very important for us, is not studying at Christmas because the exams are in December.

From a practical point of view, if you are considering studying in the Netherlands, it is important to know that the application process is very different from the Spanish one. To enter a degree, or bachelors, you usually do not need any entrance exam (like EvAU or selectividad in Spain), but you need a CV, motivation letter, recommendation letters and sometimes also essays to prove your experience and knowledge. In most cases, you will also have to do an entrance interview. The admission process for master’s degrees is the same. Another thing to keep in mind is that the application deadline is usually much earlier than in Spain. For some scholarships or specific degrees, you will need to send the application in December or January if you want to start in September. The whole process is done from the universities’ websites, so if you are interested the best thing to do is to look at the websites and there you will find all the necessary information on how to apply. And as a piece of advice, start looking for accommodation soon because, as you probably already know, there is a huge housing crisis in the Netherlands and it can be very frustrating to look for an apartment.

As for our own experience studying in the Netherlands, although still scarce, it has been very satisfactory. We studied at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, the Master in Neuroscience (Cristina) and the Master in Biomedical Sciences specializing in neuroscience and international public health (Patricia). In general, we both found the university education very dynamic, collaborative, and practical. However, if we are honest, it was difficult to adapt at first. We came from studying biochemistry at the Autonomous University of Madrid (Cristina) and the University of Navarra (Patricia). There, education was based on rote learning of large amounts of scientific material. For some people, the more organized ones, this worked well enough: they started with plenty of time, set their exam dates and came up with good study strategies. Unfortunately, these were in the minority. On the other hand, the vast majority of students were unable to memorize all the details that were likely to “fall out” on test-type exams. Moreover, the memorized data were usually forgotten after the first beer and the first pincho de tortilla they had after leaving the exam. This dynamic is well known in Spain. On paper it works, but in real life, a student is unable to combine this study strategy with a healthy lifestyle for physical and mental health. The first difference we saw when entering university in the Netherlands was this. Here the format of the lectures is not extensive reading of slides and examination of only this material. Here, if there are slides, they contain pictures, graphs, drawings, etc., but hardly any print. The teachers explain the subject matter based on scientific articles, and show the figures from the articles on the slides. This encourages critical thinking and reasoning but also results in less theoretical training, as it takes much longer to explain scientific articles than to read textbooks. In addition to this, teachers make much use of online tools such as mentimeter that assess students’ knowledge during class and increase the participation and attention rate. We are always happy to see a mentimeter on the slides because it means that we will have five minutes of mental rest during class.

As for the exams, these are usually based on scientific articles, books and other bibliography suggested by the professors responsible for the subject. What is given in class is usually a summary of these and we are expected to expand and consolidate that knowledge on our own before taking the exam. Another important difference in teaching in the Netherlands is that the examination of the subject is based much more on group work and presentations, and a lot of importance is given to individual work and group work. This makes the Dutch very good at finding and contrasting information, solving problems and communicating efficiently in groups. A curious thing about group work is that the examiners do not only take into account the grade of the work itself. In addition to this, they also take into account the score you get from your fellow group members for the quality of your work and collaboration. And don’t think they won’t say the wrong thing, if we had to define the Dutch in one word it would be: straightforward. If they think you haven’t worked hard enough, they’ll say so. If you have not been communicative enough, your grade will reflect that. If you have been an exemplary colleague, you will know it. In this country, honesty and fairness in the workplace come first.

Another area we would like to comment on is the closeness of students to professors. In Spanish universities, the general experience is a distant and cold relationship, strictly professional. At universities in the Netherlands, the relationship with professors is very close. Several practical examples are: when addressing them, either by email or in person, it is by first name, not by last name or position. Also, in class, if you disagree with them, you are expected to raise your hand and initiate a debate (always respectfully) about the issue. This is seen as normal, not as an affront or a “lack of education”. This is not only reflected inside the classroom. From the outside, students have a great influence on the design of subjects and grades. Once a course has been completed, the university sends out an online form for students to provide feedback on the content and format of the exam. Subject leaders meet with student volunteers to discuss the results of these forms and modify subjects accordingly for the following year. This is also the case with exam formats and dates. It is possible to change them as long as there is a reasonable reason shared by the majority. The student council usually mediates these negotiations between students and faculty. In addition, the student council meets at least once a month with the faculty council to give its opinion on all matters related to the faculty. The influence of the students goes so far that the faculty councils, and even the university council, cannot approve a measure without the students’ prior approval.

Finally, we wanted to highlight two practical aspects. The first is in terms of grading. In the Netherlands, tens are very rarely given. The saying here is: eights are for excellent students, nines are for teachers and tens are for gods. The highest mark is usually a nine and a ten is achieved when you have done something extraordinary within the subject. The second thing to note is the figure of the Junior Lecturer, a teaching position within the university, specifically for recent graduates who find teaching something they would like to devote themselves to in the future. For this, however, no university teaching master’s degree or doctorate is required. These are often even closer to the students, since they are practically the same age.

We would like to conclude by saying that, in general, we believe that in Spain we are very strong in terms of content. We learn more, but at the cost of what? In exchange for very broad knowledge we sacrifice the development of our soft skills, professional values, and personal life. Studying in the Netherlands we have realized that it is possible to combine our social life with a good curriculum. However, we would like to point out that this is the limited and personal experience of a sample size n=2. Other people may have had a very different experience studying at the same university or at another within the country. But, no doubt: the best way to know is always to try!

Ref 1. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/paisesbajos

Can you help us to become more? Become a member and participate. Spread our word on the networks. Contact us and tell us about yourself and your project.

beba arlanzon

Master student in Biomedical Sciences, Neuroscience and Public Health International

She holds a degree in Philology and a PhD in Translation from the University of the Basque Country. She is currently in a period of professional transition oriented towards communication.

Cristina Boers Escuder

Biochemist (UAM). Neuroscience MSc Student at VU Amsterdam

I am Cristina, half Spanish, half Dutch. I have lived in Madrid almost all my life, and I studied Biochemistry at the Autonomous University of Madrid. There I became fascinated by neuroscience, so I decided to come to Amsterdam to do the Master in Neuroscience at the VU and to explore the other part of me. It has been an amazing experience as I have met super interesting people and learned a lot. I am also the director of the activities and events department of Women in STEM. Next year, I would like to stay here and do a PhD studying astrocyte-neuron communication, my passion within neuroscience.